By James Brown

The HERA-funded research project Intoxicating Spaces (2019–22), on which I was fortunate enough to work and which explored material environments for the production, trafficking, and consumption of new intoxicants in Amsterdam, Hamburg, London, and Stockholm 1600–1850, coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and its attendant lockdowns. An avid user of bars, cafes, and restaurants in Sheffield in the UK, where I live and where the project was headquartered, I admired and became fascinated by the creative ways in which these hospitality businesses adapted and repurposed outdoor spaces – gardens, pavements, patios, roads, and yards – in response to bans and restrictions on indoor socialising (measures which have a long historical precedent in plague time). These present-day crisis developments inspired me to take my own research on early modern London outside into the open air.

There were various kinds of al fresco food and drink retailing in the early modern capital, from the street-sellers recently investigated by Charlie Taverner and Freya Purcell, to the temporary (or, in modern parlance, ‘pop-up’) booths that sprouted in the royal parks and during fairs. However, one of the most common was the tea garden, a distinctive species of space that flourished in the metropolis – as in other cities across the continent – between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries. The significance of these environments, especially for the enjoyment and assimilation of new intoxicating substances, has yet to receive the historiographical attention it deserves. Environmental and garden historians have tended to focus their energies on large-scale, well-documented pleasure gardens such as Marylebone, Ranelagh, and Vauxhall. Most historians of intoxicants and intoxication, meanwhile, have generally ignored tea gardens in favour of the more familiar indoor locales of alehouse, coffeehouse, household, inn, and tavern; they get only a single passing reference, for example, in this excellent recent monograph on tea. This is possibly because, faced with London’s spiralling population and growing pressure from property developers, most of them disappeared from the urban landscape over the course of the nineteenth century.

The heyday of the metropolitan tea garden was the eighteenth century into the early decades of the 1800s. Estimates of their numbers vary, from c.200 at the top end to the more conservative figure of 65 proposed by Penelope Corfield. I’ve identified around 90, the locations of 81 of which I’ve been able to pinpoint with some accuracy using the visualisation software Tableau. As the interactive map shows, tea gardens were broadly dispersed across the capital and its rural hinterland, although in the terminology of human geography five broad ‘clusters’ can be identified: there was a particularly concentrated central group around Clerkenwell; a Marylebone group; a Chelsea group; a south of the river group; and two outlying Islington and Hampstead groups scattered along the leafy roads and arteries leading out of the city to the north. Within the overarching rubric of tea garden, however, surviving visual evidence indicates there was a huge amount of spatial variety; compare Copenhagen House in Islington, a huge semi-rural tavern with extensive grounds, to the much more bounded setting of the Yorkshire Stingo public house and tea gardens in Paddington.

Food and drink was central to the offering, and – as their name denotes – tea gardens were most closely associated with a new generation of New World intoxicants, especially caffeinated beverages, and particularly tea. There were three main ways in which they fostered the incorporation of these novel substances into the diets and habits of Londoners. First, they were highly visual environments, dedicated to spectacle, the gaze, and the pleasures of the eye. Perhaps more so than any other kind of space, this made them ideal viewing platforms for the conspicuous consumption of fashionable new commodities like coffee, sugar, tea, and tobacco, and the cultivation of polite rituals surrounding them (the tea arbour or trellis is a recurring motif within eighteenth- and nineteenth-century century artistic discourses). Second, the availability of new intoxicants at the handful of spa gardens formed around natural springs – like Bermondsey Spa tea gardens, here described by the printer George Smeeton – would have strengthened existing conceptual associations between coffee, tea, tobacco, and good health. Third, while not wishing to labour the obvious, tea gardens were botanical. Their lawns, shrubberies, and trees offered a carefully curated, sometimes exotic rusticity, while those in outlying locations to points north, east, west, and south offered vantage points from which the sprawl of the global imperial city could be appreciated and admired. They were therefore almost archetypal settings for the enjoyment of agricultural derivatives from tropical climes.

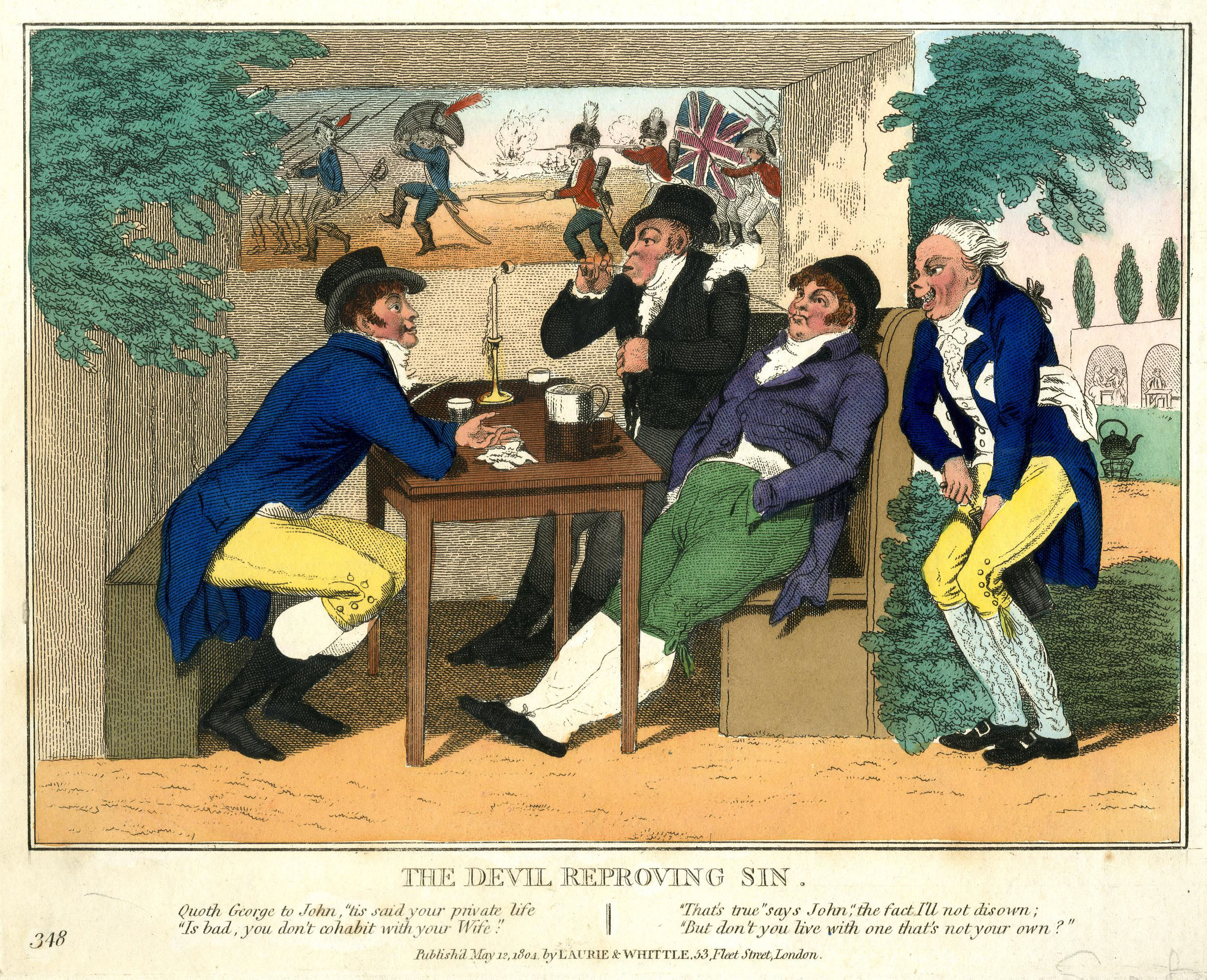

However, in characteristic fashion, tea gardens were also hybridised consumption spaces that retained close associations with traditional stimulants and intoxicating spaces. They were not standalone or sui generis ventures emerging from nowhere, but were generally opened by enterprising publicans on sites contiguous with inns, taverns, and alehouses; as well as the example of the Yorkshire Stingo above, see this drawing of the Chalk Farm tea gardens in Camden, where the outdoor space is adjacent to the colonnaded public house. As such, ‘old’ intoxicants in the form of alcohols (beer, wine, and spirits) were just as likely to be served and consumed within them as caffeinated drinks. This satirical etching, for example, depicts Bagnigge Wells, a fashionable spa and resort in Clerkenwell; while a kettle sits abandoned in the distance, a grinning waiter uncorks a bottle of wine or spirits for the three fashionably dressed male customers. This chimes with our findings elsewhere in the project; coffee’s percolation throughout provincial England, for example, was facilitated not by freestanding coffeehouses but by the creation of ‘coffee rooms’ within long-established drinking houses.